Streptococcus pneumoniae or pneumococcus is a highly contagious and potentially deadly bacterium that is responsible for up to one million deaths annually, among children under the age of five years.

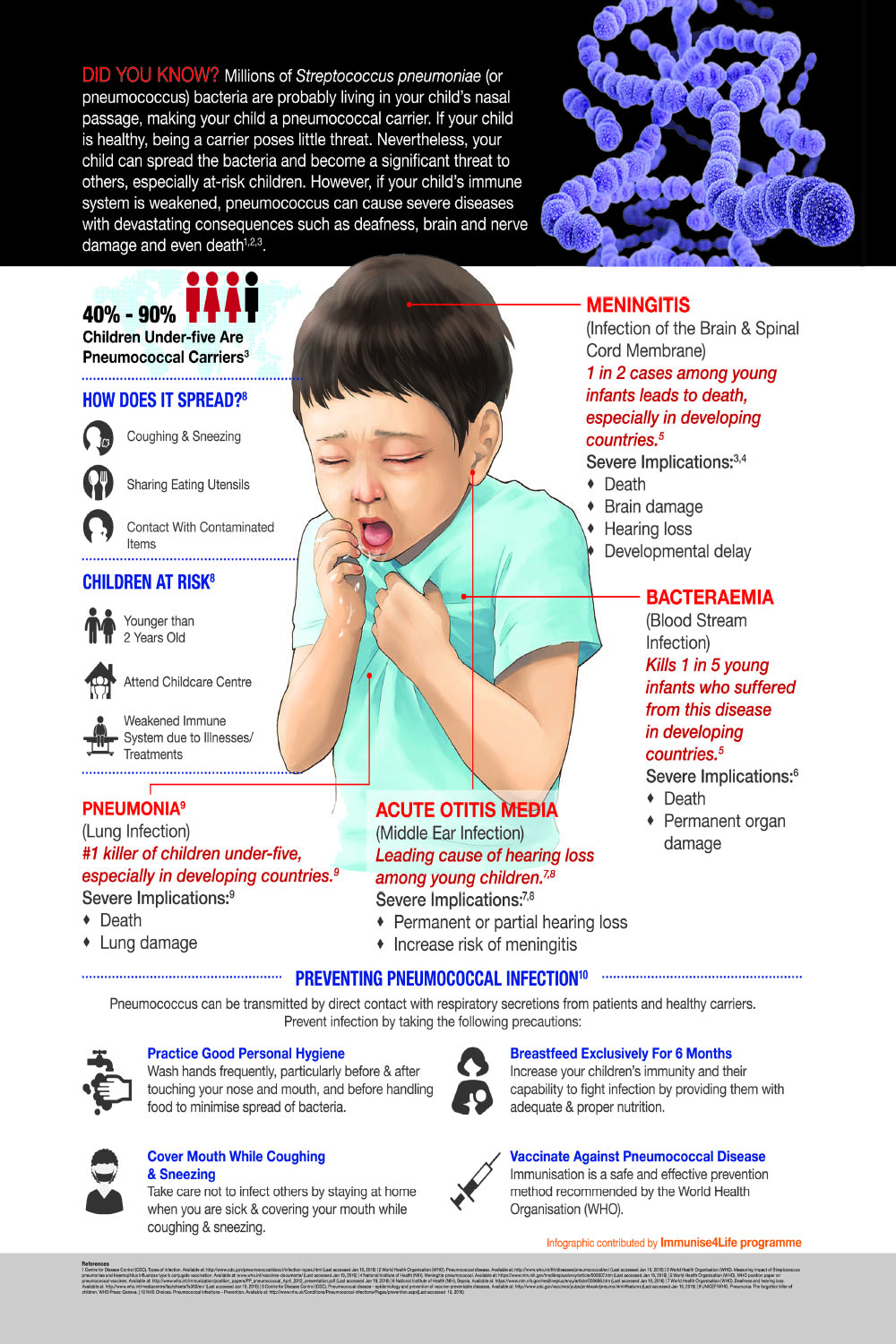

About 40-90% of children are pneumococcal carriers, with the bacteria commonly found colonising the nasal passages. Pneumococcus is transmitted easily through direct contact with respiratory secretions, including the mucous and saliva of infected individuals.

S. pneumoniae can attack various parts of the body, causing pneumococcal diseases of varying severity. These diseases range from less severe yet debilitating illnesses such asotitis media (inflammation of the middle ear) to severe and deadlyinvasive pneumococcal diseases such as pneumonia (lung infection) with septicaemia (blood stream infection), and meningitis (infection of the protective layer of the brain and spine).

Children under-five attending nurseries or kindergartens are two to three times more likely to develop invasive pneumococcal diseases and acute otitis media. Children in this age group are more susceptible partly because their immune systems have yet to mature. Furthermore, they are exposed to more carriers at nurseries or kindergartens.

The good news is that there are ways to protect your child against pneumococcal disease and this includes practising proper hygiene and vaccination. However, some parents still refuse to take preventive measures such as vaccinating their children. Some prefer to leave things to chance and fail to realise that the bacteria is like a ticking bomb. Pneumococcus may stay idle for months or years, but once it causes severe infection, it can be difficult to treat, causes hospitalisation and may have long-term negative health-implications or even lead to death.

Case #1: Literally taking your child’s breath away

According to Datuk Dr Zulkifli Ismail, “A child suffering from pneumonia often experiences high fever, cough and difficulty in breathing that will lead to prolonged hospitalisation, frequently in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), and sometimes even surgery and death.” The consultant paediatrician and paediatric cardiologist also points out that treatment of pneumococcal infection can be tricky because it may not even be recognised or diagnosed, and resistance to antibiotics is increasing.

For example, a two-year old girl, Lucy* was admitted to hospital after seven days of prolonged coughing and fever. The fever reached as high as 40°C despite her mother dutifully administering the prescribed antibiotics at home. Upon admission to hospital, Lucy* was diagnosed with pneumococcal pneumonia and, much to everyone’s dismay, her x-ray results showed that her right lung has collapsed and filled with fluid, making it extremely difficult for Lucy* to breathe. She had to have a tube inserted in her right chest to drain about 250 ml of fluid, and was then placed under close observation for two days at the High Dependency Unit (HDU) where stronger intravenous antibiotics were administered.

Thankfully, after 10 days of treatment at the hospital, Lucy* recovered with some transient psychological trauma of hospitalisation and with only a scar on her chest. Later, Dr Zulkifli discovered that Lucy* had not been vaccinated against pneumococcal infection. Lucy’s* mother said that, if given the choice, she would have vaccinated her child if only to spare Lucy* the agony of having to fight against pneumonia and not have to watch her daughter fight for her life.

Case #2: Fever should not be taken lightly

According to Dato’ Dr Musa Mohd Nordin, consultant paediatrician & neonatologist, high fever arising from pneumococcal infection may well be one of the first signs that the bacteria has spread to the brain. This disease, called meningitis, is often fatal especially in children under five years.

Dr Musa elaborates by citing a case in which a five-month-old baby girl, Adlin*, had pneumococcal meningitis within four days after the onset of high fever. Adlin* was brought to the hospital two days after her fever failed to subside despite being given medication from a clinic. Upon admission, Adlin was irritable, feeding poorly and vomiting. She was immediately placed in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), given ventilation, intravenous antibiotics and closely monitored.

Unfortunately, Adlin’s* cerebrospinal fluid test confirmed spread of pneumococcus infection to her brain and spinal cord. Despite the medical team’s best efforts, she died within 10 hours of admission.

“It is really heart-breaking to watch parents grieve the loss of a child,” said Dr Musa. “As medical doctors we know that pneumococcal meningitis is not easy to treat. That is why we would rather encourage parents to take all preventive measures, including vaccinating their children against the disease,” he added.

Case #3: Ear infections may affect language development

Infection reduces hearing ability because the pus developed in the middle ear prevents the eardrum and middle ear bones from moving as freely as they should. In a worst case scenario, too much pus can put pressure on the eardrum and eventually cause perforation in the eardrum. Hearing loss from otitis media may range from mild to moderate, to severe to profound. If this hearing loss occurs at the time when it is crucial for speech and language development, the child will most likely end up with speech and language disabilities.

Often, such speech impairments also lead to learning difficulties and poor academic performance. Such problems were experienced by Zikri*, who was susceptible to repeated ear infections from birth. Zikri* had speech delay and was unable to speak properly even by the time he enrolled in his first year of primary school. For his first assessment at school, he did so poorly that the teacher decided to place him in a special-needs class. His mother, not realising that his speech delay may have been caused by his ear infection problems, did not consult with ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist until the following year, when Zikri* had an episode of severe and painful ear infection. Upon treatment, Zikri’s* hearing improved, as did his grades.

An article contribution by Malaysian Paediatric Association under the Immunise4Life programme, supported by GSK.

For more information: http://ifl.my/diseases_category/pneumococcal-disease/

*Disclaimer: Names have been changed to protect privacy